In September 2020, my two suitcases and I set off on the journey to Oslo. Not even eight weeks earlier, I had been chatting with a friend from Oslo and almost jokingly wrote: “If you hear of a free apartment, think of me.” He replied that his would soon be available for about four months. That laid the foundation for the project “Emigrating to Norway.”

In the middle of the pandemic and just two days before the borders closed, I managed to get to Oslo and moved into my friend’s apartment. At first, only temporarily. After four months, I had to decide: do I want to stay here or go back to Berlin? I decided to stay for at least a few more months and found a small apartment in my favorite district, Grünerløkka. Because I wasn’t completely convinced by Norway just yet. Scenery-wise, it was everything I had imagined. What I struggled with, however, was the reserved mentality.

Content

Norwegians’ secrecy: pandemic-related or mentality?

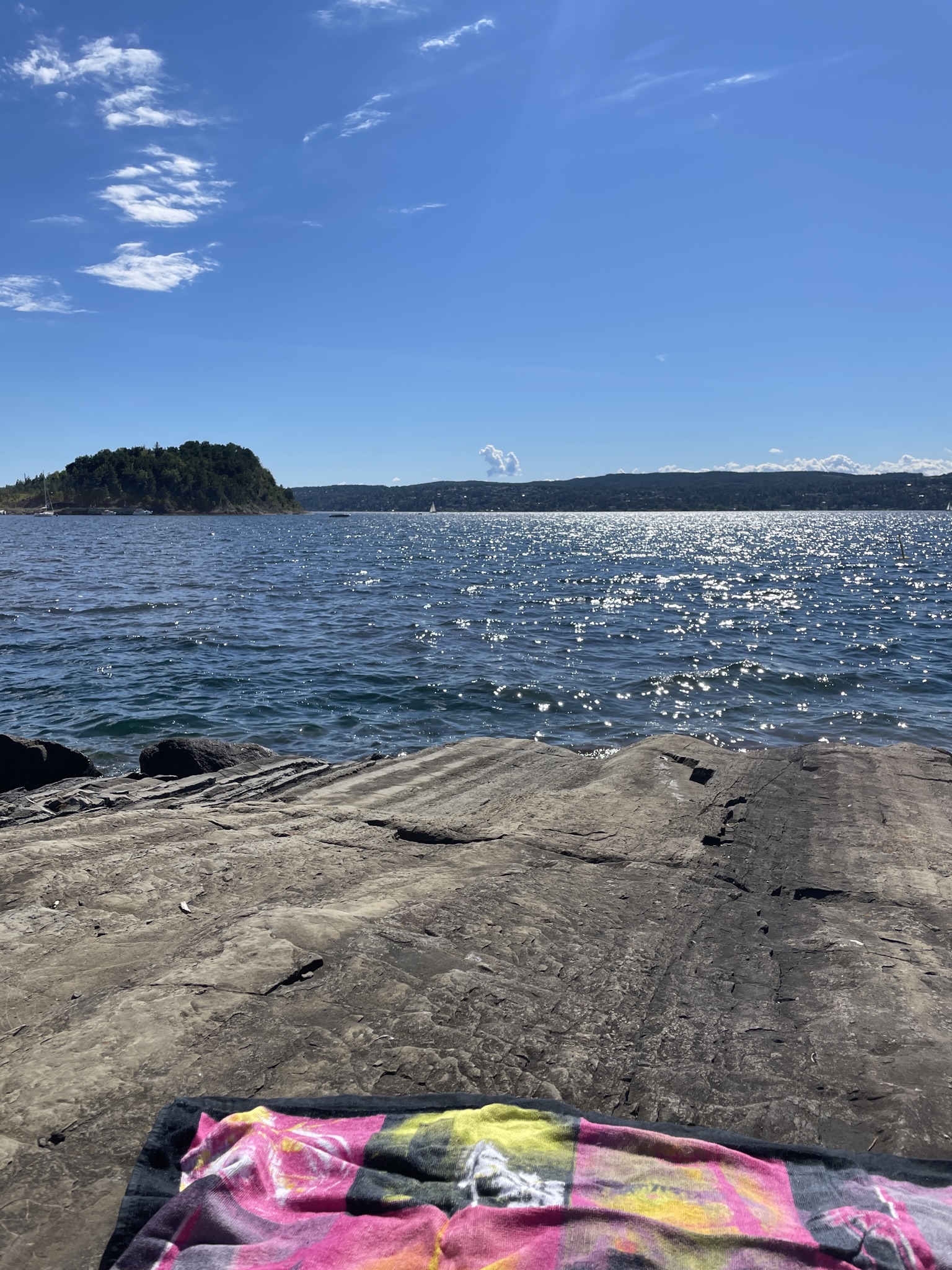

I initially blamed it on the pandemic, because moving in the middle of it doesn’t exactly cast the Norwegians in the most “normal” light. Restaurants and bars were closed for a long time, so the opportunities to meet people were limited. So I threw myself into new hobbies like cross-country skiing, revived my ice skating and skiing skills, hiked a lot, and explored the city and the surrounding area. I was probably fitter than I’d ever been in my life. It helped that we had a fantastic winter and an even more fantastic summer. I made more and more contacts, but very few were Norwegians. When I did meet Norwegians, they were usually partners of friends.

I also tried to make professional contacts, both as a freelancer and in part-time jobs, only to find out that, as a non-Norwegian, I was being offered a significantly lower salary or day rates than Norwegians. A certain bad aftertaste remained because I wasn’t an isolated case. I heard the same thing in expat Facebook groups and among acquaintances.

As an expat, you often feel lonely at first

Lower pay, while at the same time being forced to rent—whereas most Norwegians buy or have had their parents buy for them—keeps putting you in a position where you feel as poor as a church mouse. When you also have to fork out 10 to 14 euros per beer, it’s inevitable that money is constantly on your mind. Up until then, I had been in the privileged position of always getting by well with my income and not having to worry about money.

Before emigrating to Norway, I had thought that nature was the most important thing to me and one of the main reasons for the move. But after a few months, I realized that going out, having a few beers with friends, or going out for dinner was just as important a part of my life. I caught myself missing dining out or having two or three beers now and then. Instead, people meet at home with supermarket beer. Sure, that’s nice too, but it’s not really a way to make new connections. I increasingly felt lonely.

Then there were always highs, when I went on trips into the green or the snow, with skis or a tent. But in the end, something was always missing, and the constant worry about money hovered over me like a sword of Damocles. Still, I told myself: “It’ll work out.”

For reference: for my 40m² rental apartment, I paid 14,000 NOK. Without electricity. That already hurts, but at least it’s 40m² and my big couch fits inside.

In early December that year, after 1.5 years in the apartment, my landlady contacted me. Her interest rate had increased along with the “felleskostnader” (like utilities), so she would increase my rent by 11% starting the following month. That would make my rent 15,500 NOK. Without electricity, and heating in poorly insulated houses is done with electricity, that’s when I made the decision to move out of the apartment and declare the project “Emigrating to Norway” as completed.

The decision is made: I’m moving to Sweden

Shortly after I made the decision, Swedish friends reached out to me, asking when I’d be coming back to Sweden, with a winking smiley. Then the British agency I’d been working for since May offered me a permanent position. They had only opened an office in Stockholm a few weeks earlier. And suddenly everything was clear: I’m moving back to Stockholm.

From then on, everything moved quickly: at the beginning of December, I gave notice on the apartment, accepted the job with the agency, and wrote to landlords in Stockholm. By 30 December, I had an offer for a central, brand-new apartment with a balcony—bigger than my Oslo apartment for less rent. And when things run like clockwork, you know you’ve made the right decision.

Emigrating to Norway: What remains after 2.5 years in Oslo?

What remains? A deep sense of gratitude for the adventure of the past 2.5 years. Unbroken love for nature and all the opportunities I had to experience it. I have:

- lived in 3 apartments

- had great landlords

- worked freelance

- worked at a Norwegian startup

- worked at a fancy bar where I learned a lot

- learned to cross-country ski

- made valuable friendships, for example with Maren from Neuschnee, also an expat from Germany.

Still, I’m looking forward to the new adventure in Sweden, even if it means starting again, more or less, from scratch. The big difference, however, is that this time I have perspective. I can apply for a home loan and actually find apartments that are larger than 23m² and centrally located. I have a steady income and can take paid vacation. Beer starts at €3.50 and there’s a lot more going on in the foodie scene too.

What I had misjudged before emigrating to Norway were mainly two things: the role of EU membership for a country, and the assumption that Swedes and Norwegians are similar. Because Norway isn’t a member of the EU, the variety of products is significantly lower. Import costs are high, which means that even if my family wanted to send me something, the shipping was insanely expensive, and sometimes customs charges were added. And when something is sold out due to the season, like ice skates, it’s sold out. Nationwide. And Amazon doesn’t exist.

My flawed assumptions

After living in Stockholm for 4.5 years, I naively assumed that Swedes and Norwegians, as neighbors, were quite similar, just like their languages. I couldn’t have been more wrong. That would be like lumping together Germans, Austrians, and Swiss. The differences are sometimes subtle and sometimes glaring. Glaring especially when it comes to mindset, though I can only speak from personal experience. I perceive the Swedes as more “European” and open-minded than the Norwegians.

When I asked my Norwegian friends why they would vote against joining the EU, they unanimously said: “Why should we? We have everything we need, and Norwegian products are enough for us.” Of course, this statement mainly refers to product variety, but it reveals so much more about the mentality: we prefer to stay among ourselves. And unfortunately, I often had that feeling over the past 2.5 years. A family friend who has lived here for 25 years likes living here, but says she still feels like a stranger. But she’s come to terms with it.

Would I do it again?

Absolutely! Because only if you try, you become wiser and don’t end up asking yourself “what if?!” I’m grateful for every experience, professional and personal. Because in the end, that’s what emigrating is about: a personal experience. It’s not that something is wrong with Norway. Norway and I just weren’t the perfect match, because I was missing too much and had to make too many compromises for my liking. A lot of things would probably have been easier with a (Norwegian) partner. Still, I will return regularly, because nature is indescribably beautiful.